In the 1960s, educators and reformers sought solutions to a persistent problem: why did so many English-speaking children struggle to learn to read? Among the most ambitious efforts was the Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA) — a specially designed alphabet intended to make learning to read easier and faster. Though the ITA saw widespread trials and generated significant debate, it ultimately faded from classrooms. This article explores its history, purpose, and why it was ultimately discontinued.

🌟 What Was the Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA)?

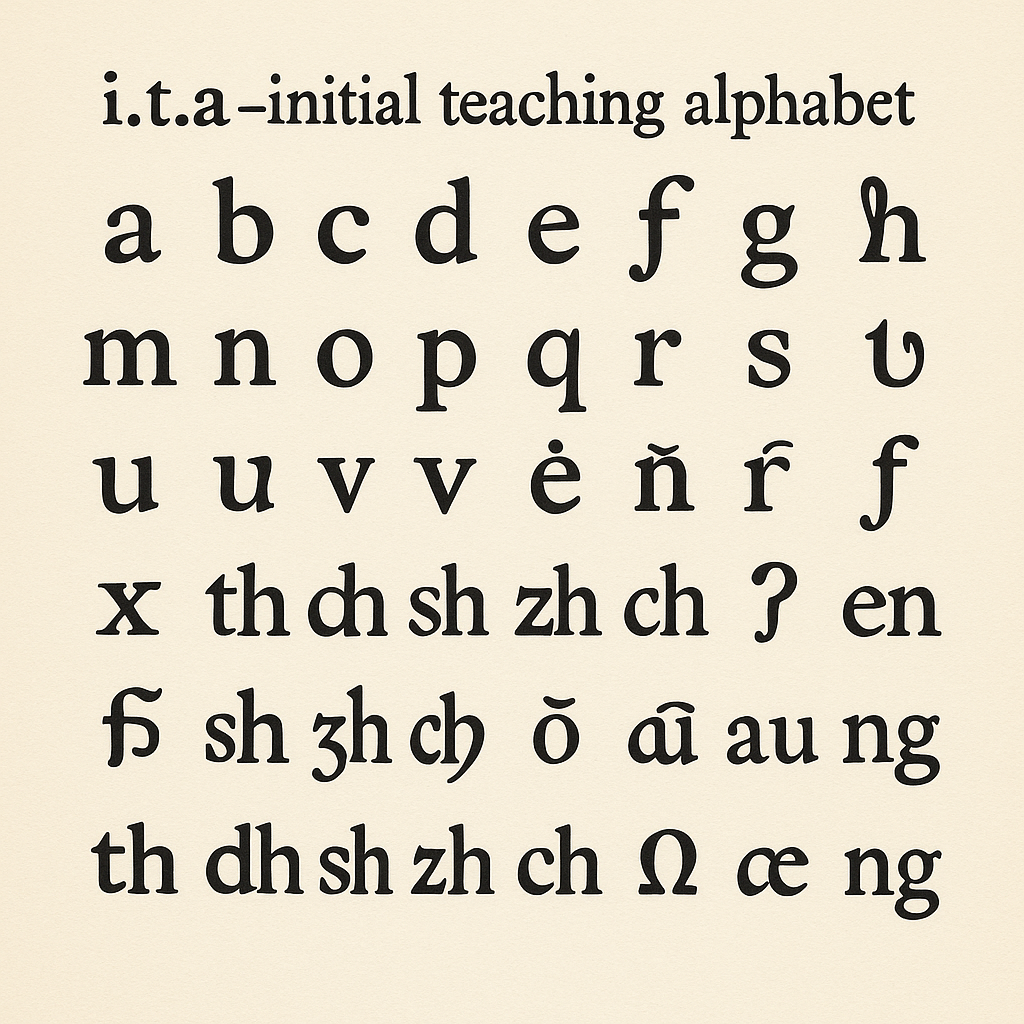

The ITA was an alternative alphabet created to help children learn to read English by representing its sounds more consistently than traditional spelling. Unlike the standard 26-letter alphabet, ITA used 44 symbols — a mix of familiar letters and new characters — to correspond more directly to the 44 phonemes (distinct sounds) of spoken English.

The alphabet aimed to reduce the confusion caused by English’s inconsistent spelling. For example, words like laugh and through, which are difficult for beginners due to irregular spelling, would appear in ITA as they sounded: laf and thru.

👤 Who Invented ITA?

ITA was developed by Sir James Pitman, a British educator, politician, and grandson of Sir Isaac Pitman (creator of Pitman shorthand). Sir James was deeply invested in spelling reform and literacy improvement. His vision was for ITA to act as a bridge, helping children master reading before transitioning to traditional English spelling.

📚 Where and When Was ITA Used?

The ITA was introduced in 1961 and adopted in numerous experimental and pilot programs, especially in:

- British primary schools

- Select schools in the United States, Australia, and a few other English-speaking regions

At its peak in the mid-1960s, tens of thousands of children were learning to read using ITA.

⚙️ How Did ITA Work?

- ITA texts (storybooks, primers, and classroom materials) spelled words phonetically.

- The 44 symbols covered sounds like th, sh, ch, long vowels, and diphthongs.

- The intention was that once children learned to decode words consistently, they could transition more easily to standard orthography.

❓ Why Was ITA Discontinued?

Despite early enthusiasm, several factors led to ITA’s decline:

✅ Transition Problems — While ITA helped many children learn to decode quickly, moving from ITA to traditional spelling often caused confusion. Students had to essentially relearn spelling rules and patterns.

✅ Cost and Practicality — Schools needed separate books, typewriters, and printing resources for ITA. This made it expensive to maintain.

✅ Mixed Results in Research — Studies found that although ITA sometimes gave children a head start in reading fluency, the advantage disappeared by later grades.

✅ Resistance from Teachers and Parents — Some educators and parents felt it created unnecessary extra steps, and worried about children’s ability to integrate into standard reading and writing.

✅ Shifts in Literacy Education — The rise of phonics-based teaching methods offered simpler, less disruptive ways to emphasize sound-symbol relationships.

🔍 Legacy of ITA

Although ITA is no longer used in mainstream education, it left a lasting mark. It sparked important discussions about:

- The difficulties of English spelling for beginners

- The role of phonics and sound-symbol correspondence in literacy

- The balance between innovation and practicality in education

Elements of ITA’s goals live on in phonics curricula and spelling reform advocacy.

Well-Intentioned with Some Success and Lead the Way for Other Innovative Teaching Methods

The Initial Teaching Alphabet was a bold, well-intentioned attempt to improve literacy, and its brief lifespan offers valuable lessons about educational innovation. While ITA itself didn’t last, its influence helped shape modern approaches to reading instruction.