How do we learn to read — and who decides how it’s done?

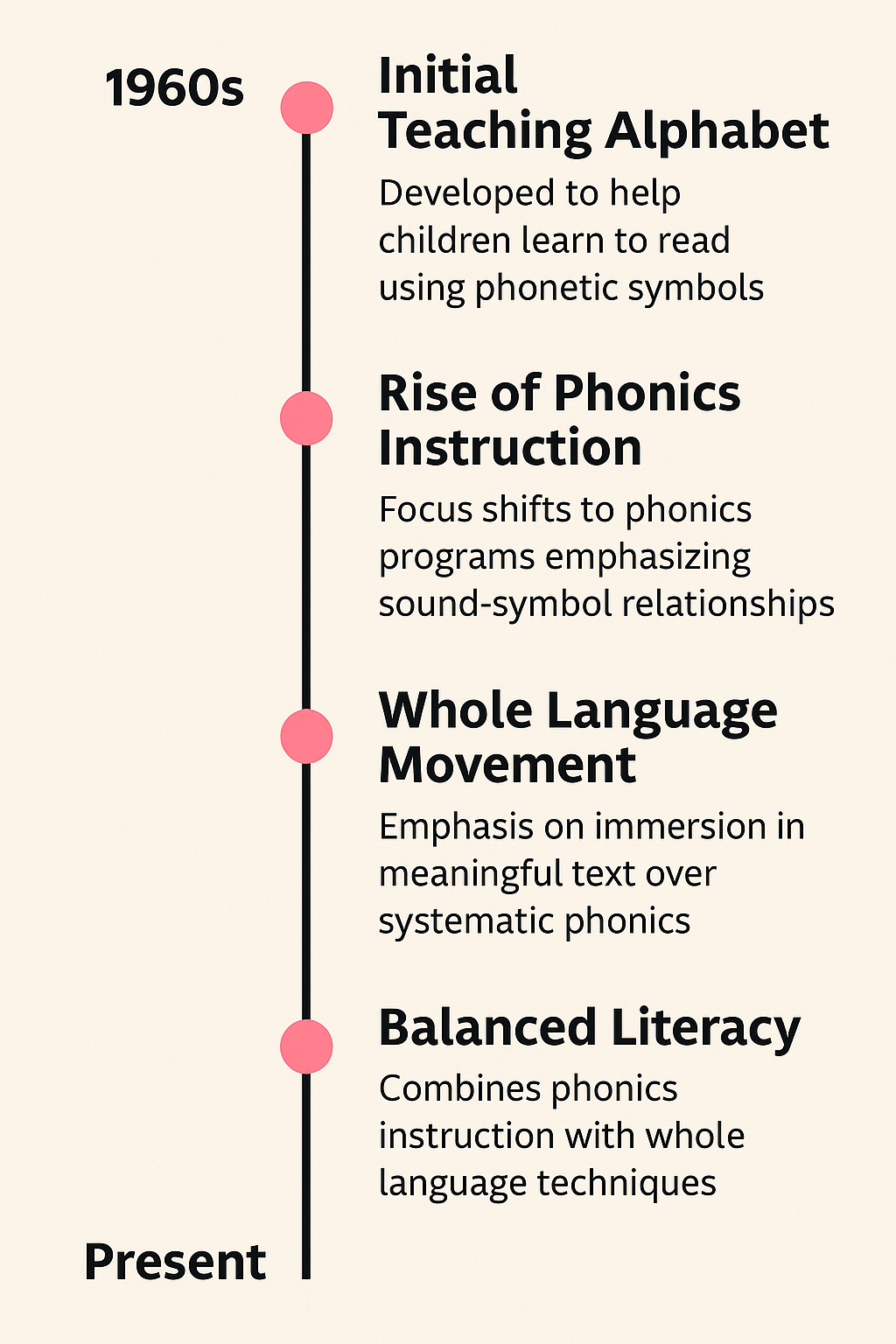

In the early 1960s, a bold experiment called the Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA) aimed to change the way children in English-speaking countries learned to read. By redesigning the alphabet itself, educators hoped to eliminate the confusion caused by irregular spelling and give students a faster, easier start.

It was a dramatic idea — one that briefly took hold in thousands of classrooms before fading into obscurity.

But ITA is just one chapter in a much larger story. Over the past sixty years, reading instruction has shifted repeatedly, shaped by battles over phonics, meaning-making, brain science, and classroom ideology. For writers and authors, understanding this history offers more than context — it reveals how entire generations of readers (and future writers) were shaped by the way they were taught to make sense of words on a page.

This article begins our chronological journey through that history — starting with the alphabet that tried to fix English.

🔤 What Was the Initial Teaching Alphabet (ITA)?

The ITA was created in the UK by Sir James Pitman, grandson of shorthand inventor Isaac Pitman. Launched in 1961, the system expanded the standard 26-letter alphabet to 44 characters, matching the approximate number of phonemes (speech sounds) in spoken English.

The goal: eliminate confusing spellings like knife, thought, or laugh and teach kids to read using phonetic symbols. Once children had mastered reading fluently, they would transition to standard English spelling.

Thousands of British, American, and Australian children learned to read using ITA texts, which were visually distinct and clearly phonetic.

📉 Why Was ITA Discontinued?

Despite promising early results, especially in boosting reading confidence among beginners, ITA’s use declined by the early 1970s. Here’s why:

- Transition Troubles: Moving from ITA to standard spelling proved harder than expected. Children had to relearn spelling patterns, which sometimes slowed long-term progress.

- High Costs: Producing new materials, books, typewriters, and teacher training for a separate alphabet was costly and impractical.

- Mixed Research Results: While early reading gains were common, studies showed no long-term advantage by the upper elementary grades.

- Resistance from Teachers and Parents: Some educators felt the system created more problems than it solved, and parents struggled to support learning at home.

By the mid-1970s, ITA was largely phased out — and no full alphabet replacement has been introduced since.

📚 What Came After ITA?

The fall of ITA didn’t end the effort to improve reading instruction. Instead, attention turned to how children were taught using the traditional alphabet.

Here’s how literacy education evolved in the decades that followed:

🧱 1970s–1980s: The Rise of Phonics

After ITA, many schools doubled down on phonics, explicitly teaching children how letters and letter combinations represent sounds. Programs focused on:

- Sound-symbol relationships

- Decoding practice

- Controlled vocabulary texts

This method built on ITA’s core insight, phonemic awareness is crucial, but without needing a new alphabet.

📖 1980s–1990s: The Whole Language Movement

In contrast to phonics, the whole language approach emphasized learning to read through:

- Exposure to rich, meaningful texts

- Guessing unknown words using context and pictures

- Writing and storytelling from the start

While popular in teacher education, this approach was often criticized for downplaying phonics. Many children, especially struggling readers, were left behind.

⚖️ 2000s–Present: Balanced Literacy

In response to the "phonics vs. whole language" debate, schools adopted balanced literacy. Blending included:

- Systematic phonics instruction

- Guided reading and writing

- Vocabulary development

- Independent reading time

Though widely adopted, balanced literacy programs remain under scrutiny, especially regarding how much phonics they include in practice.

🔁 The Current Shift: Back to Structured Phonics

Today, many educators and policymakers are re-emphasizing explicit phonics, especially in response to research on the “Science of Reading.” Recent curriculum shifts include:

- Systematic phonics programs (e.g., Jolly Phonics, Fundations, Sounds-Write)

- Targeted support for struggling readers

- Greater emphasis on decodable texts over leveled books

🔍 What Did ITA Teach Us?

Though the ITA is no longer used, it left behind important lessons:

- Spelling is a barrier: English’s irregular spelling still challenges learners. ITA helped spotlight this issue.

- Sound-symbol consistency matters: ITA’s biggest contribution was highlighting the value of phonemic awareness in early reading.

- Innovations need to be sustainable: ITA showed that even effective ideas must be practical, affordable, and easy for teachers and families to use.

Though the Initial Teaching Alphabet ultimately failed as a lasting solution, it left behind important lessons — about how children learn, how language functions, and how difficult true reform can be.

What followed in the decades after ITA was no less dramatic. From the rise of phonics-based instruction to the idealistic — and often disastrous — Whole Language Movement, the history of how we teach reading is filled with conflict, innovation, and unintended consequences.

In the next installment, we’ll explore the phonics resurgence of the 1970s and 1980s — and how it tried to rebuild literacy from the ground up.